Great elephants, little pygmies, precious diamonds and the love of the missionaries.

Sometime during the Creation – shall we say around the fifth or sixth day? – God was passing the intersection of the 2nd Parallel North and the 16th Meridian East. I know of course that at that time the global reference points had not yet been quite so closely defined. And the Good Lord certainly didn’t need them to guide Him over the earth, which He had just created. But it’s just to help you understand precisely where He was at the time. For it was here, whether through tiredness from all the work of the previous few days or simply because He didn’t as yet have seven billion people to worry about, that He decided to stop and rest a while, and fell asleep. However, He hadn’t noticed that there was a hole in the bottom of the sack of His imagination, from which there issued rivers and waterfalls, mighty trees, precious stones and creatures of every shape and color.

And when He awoke, it was too late to put everything back in the sack again. In fact the monkeys, swinging through the lianas, were by now already playing with the sack from which they had just emerged. God smiled in amusement and decided that the monkeys had turned out really well. He called what he had created the “Forest” and decided that he would need someone to take care of all that beauty. So then he created the pygmies, one of the most gentle and peaceable peoples on earth. God gave them the keys to the forest and left that place, somewhat reluctantly, in order to start devoting himself to the problems of mankind, who soon after that had built their first cities.

All those wonderful things, just around 500 km away from where I was living, surely deserved a personal visit. And so we decided that a little trip to this part where God had rested awhile so many centuries before, might be the ideal spot for us also take a little break and relax a while, after the stresses and strains of the first term of the academic year.

First stop on our long journey was Bambio, close to the Lobaye river, one of our favorite stopping off points in the region. No sooner had we arrived than the family of Brother Régis, in addition to putting their whole house at our disposal, had offered us excellent locally produced coffee. The sun hadn’t yet set, and so we took the opportunity to have a good dip in the river. The next morning, before continuing our journey, we celebrated Mass in the village church. But of course in Bambio it is impossible to celebrate Mass except in a solemn manner, and all the people turn up in large numbers. Priests are rarely seen here, so you can imagine what it’s like if you arrive with a whole convent full of brothers. The ‘continental breakfast’ provided in Bambio, needless to say, included manioc and fresh game, hunted the day before.

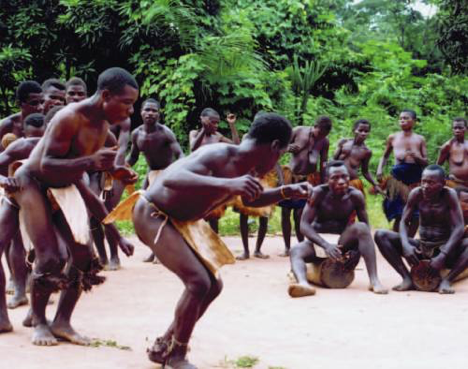

In the afternoon we arrived in Belemboké, a mission station serving only the pygmies on the edge of the great forest. The only non-pygmies present in the village were two African priests, Padre Anselm and Padre Serge, three Latin American sisters, Sister Melanie, Sister Alba Maria and sister Margarita, and the teacher at the primary school. The pygmies, as my brother missionaries explained to me, are the true inhabitants of Central Africa. It is here that they were truly placed by the good Lord, whereas the other inhabitants

of the country are in fact members of the Bantu peoples, who arrived in Central Africa as a result of a series of migrations.

The parish and the village in Belemboké came into being at the same time in 1973, on the initiative of Padre Lambert, a brave French missionary. He had noticed that the pygmies very often lived in subjection to overlords belonging to other ethnic groups, almost like slaves. In creating a parish for the pygmies alone, this priest at the same time in fact enabled the birth of a pygmies-only village, as all around the church they began to build their typical little huts of woven branches, covered in leaves, in the shape of an igloo. And with all new respect to those who, somewhat hastily, maintain that evangelization was one of the causes of the extinction of indigenous cultures, in reality this priest gave the pygmies, along with the Gospels, their true liberty and dignity, preserving both their culture and their traditions. And as one of the most interesting aspects of pygmy culture, in a context in which polygamy was widely practiced, he found that they observed a rigorous monogamy which married extremely well – and it is well worth pointing this out – with the Christian view of marriage.

Needless to say, though, the initiative of Padre Lambert did not altogether please those who had thereby lost their free labor force, and he received a number of threats. But the man who intervened and came to his defense was Bokassa, the ‘famous’ ruler of what was then known as the Central African Empire. He declared that if anyone did any harm to this priest, it would be as though they had done the same thing to the Emperor himself. From then on these little lords of the forest were able to continue living happily and in peace, though of course they knew nothing of the umpteenth, and dubious, peace accord for Central Africa that had just been signed in Khartoum.

After spending the night among the huts of the pygmies, we set out for Bayanga, where we planned to visit the Dzanga-Sangha National Park. This park lies deep in the forest of the Congo River basin, in the furthest southwest extremity of the Central African Republic, wedged between Cameroon and Congo Brazzaville. The objective of our excursion was to locate a colony of elephants and observe them from close up. We travelled on foot through

a stretch of dense forest. Our guide, assisted by a pygmy at the head of our group, gave us some instructions as to how to behave if we should come face to face with an elephant or a gorilla. As for the hippopotamus, he had no particular instructions to give us, but simply told us that it is better not to come face to face with them at all. In the end he asked us to remain silent to avoid attracting the attention of the animals. And my confreres and I immersed ourselves in a silence still stricter than we are required to observe in the monastery, in the evenings, after the prayer of Compline. A few meters further on, while crossing barefoot over a small stream, we saw huge footprints in the ground. Our guide was not kidding us – the elephants had indeed passed through here shortly before us. After almost an hour’s walking, we climbed up onto a viewing platform built specially for the purpose of watching these most magnificent of God’s creatures, which were accustomed to come here to a watercourse around midday to drink.

It was an impressive spectacle, far exceeding our expectations. There were around a hundred elephants there. But according to our guide, within this one area of forest they have counted around 4000 elephants altogether. An amazing heritage that makes this little and uncontaminated corner of nature somewhere almost unique in the world, and one that certainly held our attention for several hours.

In the afternoon we headed back north. Once again, we crossed through the tropical forest. To describe it as luxuriant would hardly do it justice. Our route followed a little trail of red earth, that seemed to timidly ask permission of the majestic trees and shrubs, with their great leaves, which towered above us with lofty pride like plumed sentinels, as though offended by our very presence. Finally, we arrived in Nola, where we spent the night. Nola is a picturesque small town, situated at the confluence of the Kadeï and Mamberé

rivers which together form the source of the great Sangha River, the undisputed kingdom of vast numbers of hippopotami. At the point where the two rivers meet there is a small island, covered in large trees and inhabited by monkeys, which was once the site of the town prison. In order to reach the ancient mission station, founded in 1939 and situated on the other side of the river, we had to drive our vehicle onto a barge, bobbing on the river. We arrived almost as the sun was setting and were welcomed by Sister Ines, an elderly Spanish nun who had prepared us a meal of antelope and shrimps for dinner.

Next morning, walking through the town, we were astonished by the sheer number of ‘bureaux d’achat’ selling gold and diamonds on every street corner. For in fact we were in one of the many zones in Central Africa where the ground beneath us is particularly rich in these precious minerals. And it is a painful thing, both to me and to my confreres, to ask ourselves the frustrating question as to why this country, which literally sleeps on gold and diamonds, should be condemned to live in such extreme poverty while others alone are able to profit from its riches.

At midday we arrived in Berberati, one of the largest cities in Central Africa. We were invited to lunch by the youngsters of the Centro Kizito, an initiative established to rescue children and young people who were victims or perpetrators of violence, many of them orphans and some of them former members of armed groups or youngsters who have spent terms of varying length in prison. Sister Elvira, an Italian missionary sister who doesn’t mince her words and cannot stand orphanages, is the originator of this community, which seeks to restore their dignity to dozens of children by helping them to learn a trade, agriculture, music, sport and above all the art of living together without hurting one another.

“Sara mbi ga zo – Help me to become a man” is the demanding motto of this ambitious initiative that has been driven with such tenacious courage by Sister Elvira for several years now, with the help of several families and in the face of not a few difficulties. One of my confreres, after visiting the center, proposed Sister Elvira as president of the Central African Republic, even if only for a single term. I doubt very much if Sister Elvira has any ambitions in this direction, but at any rate, just this year the president of the Italian Republic formally recognized her achievements by awarding her the honorary title of Commendatore of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic.

In the Cathedral of Berberati we met the young Bishop Dennis Agbenyadzi, who is originally from Ghana and who entertained us by telling us a few of his own missionary experiences, in particular involving the eight years he spent as a parish priest among the pygmies of Belemboké.

After this we headed still further north and halfway along our route, made a stop at the Touboutu Falls. Next we arrived in Carnot, another centre of the gold and diamond trade. We were welcomed by Padre André, an elderly missionary originally from Belgium. We visited his church of Notre Dame de la Mamberé which, though sadly now in a poor state of repair, stands like a gem of mediaeval art that has landed by chance like a meteorite in this spot. Travelling onward towards Baoro, our penultimate stop and the place where we first opened our mission in 1973, we became immersed in a fascinating and animated debate about nature, history, beauty, and the emotions of a European and those of an African… De gustibus non est dispuntandum, as the ancients used to say. But I was not among the ancients here, but among the young, for the most part, and the argument became quite heated, to say the least. In the end, though, my opinions and my aesthetic canons were quite plainly in the minority. So I confessed myself defeated and we moved on to less contentious issues.

In Baoro, as guests of our Carmelite confreres, we visited the catechists’ school, which had just been reopened. It was started originally many years ago by our confrere Padre Nicolò, the founder of our mission there, but closed again shortly after. Now it has been revived, thanks to the determination of Padre Odilon, who is dedicating himself with passion to the formation of the ten catechists living there with their families.

As we travelled the last few kilometers back to Bangui I thought back over the places and above all the people we had met during our journey: the missionaries, both men and women, who have fallen in love with this country and who, like hidden diamonds, are working quietly and without fuss for the Kingdom of God. To each of them I had put the inevitable question: “So how long have you been here then?” An indiscreet, even impertinent question, as if I were asking for the combination of a strongbox that didn’t belong to me. The missionary in question would smile and close his or her eyes – as though to show the need to look back over each year spent in that place – and then say the number, humbly yet proudly at the same time, as though it were a secret he or she would have preferred not to reveal, as though it were the number of carats of the most precious diamond, the secret of their own life, given for the Gospel and for this people.

Warmest greetings from Bangui

Padre Federico